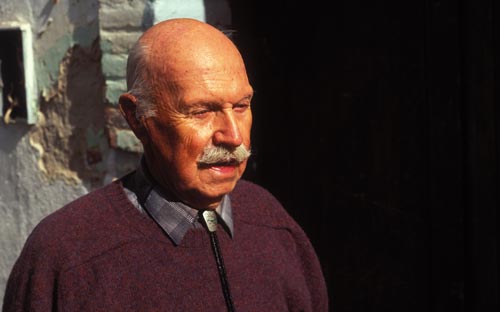

Levant Alcorn

Last modified: February 14, 2014And along came a man named Levant Alcorn…

Not until the 1950’s did a lone American, Levant Alcorn, come from Pennsylvania to the cobblestone streets of Alamos, Sonora, Mexico, and see future potential. He saw value in the plazas, arches, ornate iron-work, carved wood doors, high ceilings, five-foot thick walls and proximity to the United States International border.

He began to acquire ruined mansions. Soon, he was selling property to independent Americans hoping to realize their dream standard of living. Restoration projects began and continue today. Now, Alamos has over 200 American families as part of its social fabric.

Each wall, every window and door is a story. Where did it come from, how and when did it get here? Was it made by an Alamos or imported craftsmen?

There is a prideful sense of ownership that comes with undertaking a restoration project that in reality will never end. And there is a humble realization that the casa is really owned by history and this is but a brief opportunity to be part of a continuum of gatekeepers and masters.

Restoration-maintenance is an industry, it is a way of life. Owners, maestros, workers

and house-help are a team that can last a lifetime.

Daybreak in the Plaza is a quiet song that slowly builds into a symphony.

As the day turns from dark to light watch Alamos, Sonora, Mexico come alive. Everyday is a new start, another challenge, another opportunity. The late Levant Alcorn is seen collecting bird feathers on his morning walk around the Plaza de las Armas.

The Last time Anders and Levant spoke.

There are the few, by circumstances within, and without, their control, have a lasting impact on where they live. One such person is Levant Alcorn. He influenced a new direction for the dusty streets and abandoned ruins of Alamos, Sonora, Mexico. He visualized economic opportunities and romantic interludes. When I met Levant he was watching Alamos move on into the future, not as a king but as one who had seen it all. Levant understood he was as much a part of Alamos as the columns of his beloved Los Portales Hotel overlooking the Plaza. I asked if he had any regrets. He smiled. He did not speak, there was no need. His sparkling eyes danced away from mine.

To see more Alamos Journal pages.

To return Home.

©2013 Anders Tomlinson, all rights reserved.

(the following interview is from the Alamos History Club.)

Interview with Levant Alcorn (1989)

Interviewer: Leila Gillette

I asked my friend, Anna Stimpson, if I could meet Levant Alcorn. One day when I returned from the market at 12 noon, a man was sitting on the porch of my casita. He was slender, with a friendly, smiling face, a full military type of white mustache and bright blue eyes. He stepped to the car and introduced himself as Levant Alcorn. After I came to my senses, I asked if I might tape our conversation, as it was about articles on Alamos in magazines.

Our tape recorded interview was as follows:

Subject: Sutherland in the Saturday Evening Post. “A Visit in Ruins!”

Mr. Alcorn: That man came here to write about the Twin City of Alamos which was called Barro Yega and he was sent here I think by some radio concern in Los Angeles. And the boys, there were some other boys along, they did go to Barre Yega and they wrote on what was like television, I don’t think we had television at that time. That was bout Barre Yega, the sister city of Alamos. El Forte is an interesting city to go to. It is sixty miles.

Leila: (I talked about a trip to the mines.)

Of course the mining business was what attracted many Americans in the early days to come here. The area is highly mineralized and there were many mines at Minus Nuevas and the bigger one is at Promentorio. I think there’s three levels on La Promentario. Oh, there’s been all kinds of stories about buried treasure. And the tunnels. I think there’s tunnels under the Plaza. I think there’s tunnels to the house next door to me. Oh, it was one of the early, early houses and the only one that has the really old railings on it. It belongs to Aldolfo Guerrero. Guerrero Sign Company in Mesa (Arizona). Adolfo is an artist and he is very well educated. You’d enjoy visiting with him.

Leila: (I Asked about La Esmeralda.)

Mr. Alcorn: We sold to those people and they never changed the roof and of course the roof fell in on them and they had to put a new one on. There wasn’t too much land that goes with it.

Leila: (We had conversation about the President of Mexico)

Mr. Alcorn: He is the one who is making Alamos a National Monument instead of just a State Monument. I was here, of course, when they made it a State Monument. Soto was our governor then. Anselmo Macias was governor just before I came here.

Leila: (We had conversation about the Urreas)

Mr. Alcorn: Now those Urreas were one of the first class families, and they were some of the ones I met when I first came here. And the sister is the one that we dealt with to get the house. There were twelve heirs. There was one, we never could find him to sign. The title, they finally accepted that this one brother was gone, lost. So they accepted the eleven, and we were able to get the house. It’s a beautiful house just above the Tesoros on the corner, that the English woman owns and wants to sell. She sold it just recently. It’s #4 (Calle Obregon) right there in front of the City Hall.

Gaxiolas were the ones that owned the Hotel Alamos. There was a maid who inherited those houses. She had a brother; he was a bachelor. Gaxiola. I’ll tell you this one story. I had a big dairy back in Pennsylvania and I worked for the government back there, the Farmer’s Home Administration. It was a federal agency. One evening this chap came in. He was from Lancaster, Pennsylvania and I thought, “Someone from my state!” Although it was three thousand miles away. So Paul Robinson and I had a nice visit, and he had a very good-looking lady with him who wasn’t his wife. And he got all enthused and he wanted to buy a house and we had another man staying at the hotel – Paul wanted to know what I had for sale and what he could buy and this other American said, “Why don’t you show him that old silk mill in front of the City Hall?” We did have that for sale; and it was after dark and Paul said, “Why don’t we go look at it with flash lights?” So we went over and looked at that old silk mill and he was taken with it, and wanted to know what I wanted for half of it. Well, I’d bought the thing and paid for it – well, anyway whether I had or I hadn’t anyway, I said $5,000. So he said the next day, “I’ll take it.” Well, he went back to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that’s where he was living then in two or three months he wrote back he wanted to buy the other half, “How much do you want for that?” “5,000.” So he bought the whole thing. Well, here I had bought the two buildings for $7,000. So I had the Hotel Alamos left over and $3,000 to boot. I came out well on that deal. That just made me all the more enthusiastic to get into this ruin business down here. And I just bought and sold land bought and sold and bought and sold these ruins till we sold most all of them. Well, just as soon as we got one room fixed in that Portales, we had it occupied. In the bar there is gold wallpaper. That’s another whole story. I can tell you about that painting on the walls and getting a fellow from Mexico City to paint them. That was in the house originally. As you go in the front door, over the second arch it will be printed there that gives you the date that it was painted by hand. Originally there were four wallpaper pictures, two on each side. One was elephants in a jungle. And others tried to come off.

When I came there the first time there were soldiers quartered in the building. It was a quartel and they had a couple of parrots that would walk up and down. And the soldiers would come out and play the bugle and then march around.

Leila: Did you buy it from the city?

Mr. Alcorn: No. There was a bachelor here. He was well educated, educated in Denver. Robinson Bours of the Bours family on the corner and of course he spoke English and I didn’t speak any Spanish. We became very good friends and George stuttered a little bit and he said, we were in the Plaza, sitting on the bench in front of the hotel, and he said, “W-wouldn’t you l-like to buy a h-house here?” And I said, “Oh, I don’t know as I want to buy a house. Which one?” “Th-this one right in front. I-i-it belongs to my aunt. Sh-she lives in Guadalajara.” And I said, “What does she want for it?” He said, “Three Thousand.” I said, “I’d give two.” He said, “You want me to send her a telegram?” I said, “Yes.” He sent her a telegram and the next day the reply came back, she’d take $2,500. And then he said, “I have another little house which used to be the carriage house, C. Aurora, if you’ll give $500 for that, three thousand for the two of them.” So that was the beginning.

We only got 4 pesos and fifty centavos for a dollar (exchange at that time). And it went to eight-fifty, and then to twelve-fifty and then in a few years time. . .

Leila: (we spoke about his house restoration)

Mr. Alcorn: It still had a roof but it needed a lot of roof and I put all new roof on. Today I might not have changed all those roofs, because it had beams like that (gestures), great big ones and I don’t believe it was leaking. Oh, we thought we had to put . . . so then we went to San Bernardo and bought the beams from the Pine up in the Sierra and it’s awfully soft and then the termites would get into the ends and then they would rot off – we have a room in our house, they just put the (replacement) beams up yesterday that (the old beams) have been in only fifteen years. We have one room that is smooth underneath that is suspended by the beams on top; it’s splendid.

I wish my memory was good enough that I can give you all of these articles that you can go and look them up. You’re welcome to see what I have left in my scrapbook.

Leila: (Mr. Alcorn told me that when he came to Alamos at first, the road from Nogales south was just a dirt road.)

November 23, Thursday, 1995

When we went to Los Portales, Mr. Alcorn came down the ramps to meet us and then led us up to the Portal. Mr. Allen Pendergraft came along. He had a folder full of material for me with a very detailed history of Alamos by Mr. French, a story about Mary Aster, a story about a billionaire connection of an Alamos resident and a book about Maria Felix, the gorgeous film actress who was born in Alamos. I put the conversation on record.

Mr. Alcorn: Oh, yes! Alamos the silver city. (This refers to Rachel French’s “Alamos-Sonora’s City of Silver”}. That’s a kind of a little pamphlet and it’s very good. The history of Alamos. Rachel became a friend of ours very early. She married Chester and Chester had a little laboratory and he bought the juice from the Papaya and made a meat tenderizer out of it. He had a pretty good business in Nogales and they were one of the first couples I met when I started crossing the border. By the way, bring the book that Allen loaned me and let me show that to her (speaking to Mrs. Alcorn). Gordon just published and it’s a good one. It’s another good story of Alamos. (Mrs. Alcorn went to get the pamphlet and book).

Leila: I was going to ask you something. Was it an article in a newspaper or a magazine that made you want to come down here from Pennsylvania in the first place? Because you were quite youngish, and to leave all those cattle, which are really quite demanding.

Mr. Alcorn: I had a marvelous life in Pennsylvania. And a marvelous family and a beautiful wife and children. I worked awfully hard. I had 90 cows, seven hired men on this farm. Then I had a couple of political jobs – I worked – my father had been a Democrat all his life and they offered him a post on what was our Milk Control Commission but my father’s health wasn’t good and he said, “I don’t think I’m able to accept anything like that.” And Arthur Colger, who was the publisher of our “Cary Journal”, Cary was one of our bigger towns in our little county of Erie, he said, “Maybe there’s something the boy would like.” He says he didn’t know what there was available and I says I’d gone to Cornell a couple of years, didn’t graduate, had a little, so very soon he called and said there was a post up with the Bureau of Markets and it was the operation of the Babcock test. I had a course in that at Cornell, testing milk and its products. You know the Babcock test is butterfat content. So I had to go to different milk plants, I had half of Pennsylvania as a territory. It’s a big state. And I had that for three and a half years. Then the Republicans got in again. Lawrence was mayor of Pittsburgh and he was the first Democratic governor in something like forty years. Then Arthur H. James succeeded him and so a friend that I had made in the meantime, another farmer from down at Ringburg said, “Why don’t you come in with me. I’m state director of the Farm Security Administration and I’ll get you a job.” And I had, I think, seven counties, Northwestern Pennsylvania Office in the Post Office Building in Cory, Pennsylvania and one in Meadville, Pennsylvania and of course I had assistants and secretaries and all this business. I had that for seven years and then I resigned and I went to Canada and I imported 200 Holstein Heifers and they were bred to freshen when we wanted milk, September, October, November, December. Then we had an auction on the last day of October, it used to be I did that for about three years. Well then – here’s a chap I’d like you to meet. Allen Pendergraft.

Leila: (The interview with Allan Pendergraft I’ll transcribe separately. Agiabampo – “Chato” Almado sailed from there, that’s where they took the bars of silver. Mr. Pendergraft had a lot of nice stories. He likes San Blas.)

Mr. Alcorn: It’s been years since I’ve been there. De Cementario. Every funeral is registered in the Parish Register. The bishop is buried up in the wall in the East side, the Gospel side. North side is liturgical. The church was commissioned in 1803. The royal seal is up there but they’ve been chiseled off.

Mrs. Alcorn: The Roman numerals on the clock are antique.

Mr. Alcorn: (After discussing the AL Gordon book) I Want to write him a letter.

Leila: What brought Mr. Alcorn down here? Was it an article in a newspaper or a magazine?

Mr. Alcorn: Oh, no. It wasn’t anything. Al and I, we had, anyway, I had bought a good used Buick, and we thought we should take a trip. We went to San Antonio and we got the bug to go to Mexico. We looked at the map and there was a paved road down the East coast. “Let’s go!” So we went to Mexico. Both his wife and my wife, Gladys, were afraid in Mexico City. We happened to get there the day that Alleman became president. It was the first day of December and of course there were parades. And motorcycles and Mariaches one after another. They would crowd up to the car and want to play. The women were just frightened stiff. Aldy and I, we just loved that. So they didn’t enjoy the trip much. The result: we both went home and we both separated from our first family; I don’t think he ever had a fight with his wife and I sure never had a fight with Gladys. We came to this town and it changed my life.

Leila: Did you ever go back to Pennsylvania?

Mr. Alcorn: Oh, yes, sure I did. I had a huge farm back there. In those figures it was fifteen hundred acres. Most of them were 125. We had machines. We had just come to that. Since then all the little farms are gone. Now it’s all commercial milk production.

Allen Pendergraft: Story about Obregon’s hand. Also the cobala, the saints in the Plaza and the retribution on the people who did that. 1930. The pulling down the churches. Fr. Bartolo’s house. They burned the church papers. They had a house fire in the home of the man who burnt the Santos.

Leila: I’m in sympathy about your feeling, Mr. Alcorn, about having come down here and totally been enraptured, because that was my feeling.

Mr. Alcorn: Well, I could hardly believe it, coming through that little street, déjà vu, you’re back in the eighteenth century. I’ve worked hard driving back and forth between all those offices. I began to have stomach trouble and I got these migraine headaches. They’re awful! And I got so I had one every week. It was too much. And that was the time when Aldy and I said, “Let’s go west!” And then we had the experience in San Antonio, we said, “Let’s go to Mexico.” We were both taken with it. And when I saw Mexico and he did too, it changed his life and mine.

I’ll say this, my first wife was a beautiful woman and a wonderful girl and mother and we had five beautiful children, and they all turned out pretty good. But in all of these businesses you know, this boy, Lady was my assistant and we got into these farm organizations. And at that time that was the beginning of farm security, soil conservation, we were just at the age to get on to those committees and we spent some time in Erie which was the County Seat and we got to playing around and of course our wives didn’t like that. That was the beginning of my problem, his too. We had some good, good kiddies.

Leila: I was interested, too, to clear up in a way you’re acquiring and disposing of the ruins. Now nobody had any idea that you paid as much as you had to pay for them. There’s a general legend that you bought them for . . . We were talking yesterday about the homes you bought and how you got started on it and the amounts of money you paid for them and how you got involved in it and it seemed you carried over the same intensity that you were putting into your dairy farm in Pennsylvania, you got trapped up in.

Mr. Alcorn: The same thing! Yes. And I did the same thing back there, you know. Bought properties and made money on them and it was at a time when they were cheap. The house that my first wife still lives in is a mansion, but I liked old things. I got fascinated with antiques when I was a kid. In the barber shop where I used to get my hair cut as a kid, old Chris Cole had a little half-round Hepplewhite console. He painted it black. It had square tapered legs and a nice wide band top on it but the band was black and I would go into that barber shop and I’d look at that table and I’d wonder what kind of wood there was under it. Finally, he got so old that he retired and he lived on First Street in Watheford, and he took the table and put it upstairs in the barn. One day, I went and said, “Chris, what did you ever do with that little round table?” “Oh, it’s up in the barn.” I said, “You want to sell it?” Well, he didn’t know. Well I bought it for five dollars. It had the most beautiful tiger striped maple on this band; great big stripes like that (shows his hands). I never could find the mate to it. That was the first antique I ever bought. Then from there on I looked for nice furniture and we did have some nice things. Curly maple, which we had in that Western Reserve in Ohio. But you know the beautiful antiques that people lugged in there years and years ago, oh! And we’d find them upstairs in barns and lofts and all over.

Yes, Gladys was an Ames, the grandma came from – I can’t think of it – the old, old town in Connecticut. She had a little tiny drop-leaf table and I looked at that and I thought, “That’s something special.” Finally I bought that and it was a Pembroke, a Chippendale and it even had the little Chippendale pull handles on it, on the drawer. I had it restored and it’s a beautiful thing. Cherry. That was one of the first things I bought. Then I began to study these antiques in the “Antiquarian Magazine”. I took both of them.

Allen Pendergraft: I tell you why he isn’t a millionaire. He’s too good to the poor people. He bought a lot of property from people who were starving to death. They would have died if they hadn’t gotten money from him. When I first met Levant, they lived over here on Calle Aurora, and he and Anna Maria were taking care of a boy nine years of age who had fallen in a fire. Talk about your saints! That cost them a lot of money. The boy died anyway but they tried very hard to save him.

Mr. Alcorn: She kept him in the kitchen. I had her. She had me. It was a beautiful house. You should see it today. Don’t those two artists have it? It’s recently been sold for a hundred ($100,000). That was occupied by Obregon at the time of the revolution. Yes. Obregon stayed in Miss Marcour’s house.

Allen Pendergraft: And when Marie Felix came to Alamos she always called on Miss Marcour and played the piano. (Allen continued talking about Miss Marcour).

Mr. Alcorn: Anna Marie, why don’t you and Leila look into the house that belonged to Maria Felix.

Leila: ( We then started talking about a library of English Books).

Mr. Alcorn: We were going to donate a building to the library but I don’t know what happened to it. It never went forward.

Leila: I didn’t find how you happened to get from Mexico City to Alamos.

Mr. Alcorn: We didn’t come to Alamos that trip. This friend of mine now lives in Scottsdale. He’s twelve years younger than I am. One time . . .(Mr. Alcorn reviewed the history of his early life in Pennsylvania) He and I were always very good friends. My mother sang in the choir; his father sang in the choir. But we had both worked hard. He had his dairy. He sold the milk in bottles and I milked the cows, ninety of them. And not for him but for the milk company. So that was our life before that. We both worked hard and thought we needed a vacation. And we said, “Let’s go west!” In those days everyone wanted to go west. We started out; we didn’t know where we were going. Ended up in San Antonio one day and then where were we going? We weren’t quite ready to go home yet. Did we want to go further west? We had this big map and we looked at it. Why don’t we go to Mexcio? We’ve never been to Mexico. None of our friends that we know of have ever been to Mexico. We got to Mexico and the first day we got there was the 1st day of December. And Allemand was being inaugurated that day, and big parades! Many Mariaches in the street. Our wives, both of them were just terrified. Aldy and I were just in our glory! We thought this was just great. As a result, you know, we separated from both of our wives. He came west a little after I did, and I came here. I had, something came over me, I don’t know what it was, but I just gave up that wonderful life I had back there, and I did have a good time.

Leila: Well, I was surprised that you found this place, because at that time there was about thirty miles of terrible road to get to it.

Mr. Alcorn: It was awful. You know it took us three days to get to Navojoa from the border. We came the first day to Hermosillo. It still takes us four hours on the pavement. You know it’s quite a long distance. 175 miles? Close to it. And the next day we had to ford two rivers because those dams were not in that backed up those great wide rivers that weren’t very deep. (The Yaki, the San Miguel). Shallow, but they were awfully wide. We had no bridges so we had to get on these things, they would have two of these row boats with planks on them and they’d swing them around to the bank and one car would drive on and he’d swing around and go across and unload us on the other side. Well, you can imagine. There was thirty or forty cars. I remember one day there was about thirty standing in line waiting for those one or two pongos. Maybe there was two on that river. Just making trips across. We lost time there, you know, in comparison with which the highway is today. Takes us twelve hours to come from Tucson today. By the time you get through the border. So we stopped in Hermosillo the first night and we stayed at the hotel, the little yellow one at the top of the hill. Very soon we knew the people. And the woman was from Chihuahua from the family that’s in the new movie, “Old Gringo,” isn’t it? You must see it. Well this family in this movie, they own huge ranches – this woman is almost my age – she’s 82. She has four sons. We stayed there the first night. The next night we stayed in Guaymas and my, we were entertained there and the next day we drove only from Guaymas to Navojoa and we were all day getting there because of these rivers.

And we got into Navojoa. And it was just the smallest little village you can imagine. Forty years ago, and of course, all dirt roads because there was no paved roads this side of Hermosillo. And the bridges were not in between Hermosillo and Nogales. We went into the only restaurant, I guess, that was there to get something to eat in the evening and two other Americans came in. And they looked at us and we looked at them and finally they said, “Come on over and join us!” So we did and we had dinner together; we made their acquaintance. One was Jack Berg and the other was Alberto Maas. They lived in Alamos. They were prospectors. They were looking for silver, and they were promoting, of course, any American that came along to put a little money in with them. We weren’t accustomed to being promoted; we didn’t know anything about such things and were fascinated with these stories they told. Jack says, “Well, why don’t you go to Alamos with us tomorrow? And if you want you can go out in the hills with us, prospecting. Only 15 pesos a day for a horse, (about $2.00 then) and we’re buying provisions today here.” We were sold so we did, “We’ll just take you up on that. We’ll accept that invitation.” So the next day, Jack had an old Dodge power wagon and we drove around and gathered supplies to take out things to the places they had in the hills where they ate and stayed when they were in the hills. And we left town; it was in early January of ’46 so, and it happened to be a day like this only maybe a little more cloudy than this. And it had been cloudy all day long. As we started for the hills there was no road; it was just a path – like, you know. All the way up here. And this grade was not surveyed, was not even laid out at that time. So we just wandered around maybe hit a ranch house halfway between here and Navojoa; that was the only building there was between here and Navojoa. And it took us about three or four hours to make that trip because we went up over mountains and down into gullies and around, and at that time we had only one little station wagon to take people to Navojoa when they wanted to go and that station wagon belonged to Anna Marie’s uncle. He’s gone today. Well we got here late in the afternoon, you know, and it had gotten dark by the time we had gotten to the edge of town and there were no street lights, of course. Everything was dark. We came up this street. But they did have a few lights in the Plaza and they had an electric plant that they’d crank up, and there was lights for the center of town here and here was the Plaza, exactly as it is today, with people walking around it. Oh! The boys in one direction and the girls in another. I guess I was just taken over. (His voice shakes with emotion) I never got over it anyway! And then so where did we stay? We stayed with Alberto Maas. He had a big old hacienda out here. It was recently sold to Dawe-Kendall Dawe. Well. Kendall’s father has been in the country not as long as I have but he came soon afterward. And he was fascinated with it and he invested in it and used some other peoples’ names here and I won’t say much anymore than they took advantage of him, and you know, in those days about the only way an American could buy was to put it in trust or in confidence and put it in some Mexican’s name. And he picked one that took advantage of him and took the land away. And today it’s all that sub-division that you see on the edge of town here. That’s only part of what the Acosta’s had out of it; that restaurant on the hill is on the same land. Out there as you leave town on the right. And that’s the way I came into Alamos.

Leila: It was while you were here on that trip that someone suggested you might like to buy a place?

Mr. Alcorn: George Robinson-Bours. He was the one who always met the Americans because he was educated in America; he spoke English. He was muy bueno, a nice man. His aunt was an Almada. His grandfather was Jose Maria. He was the one who was the wealthiest. He had a house this side of the City Hall. I have one daughter who lives there today. The big house, which included all three of the Portales, the house on the corner.

Leila: That faces the East?

Mr. Alcorn: That faces the Plaza.

Leila: That was owned by Ignacio, the oldest brother?

Mr. Alcorn: The fourth one was the Bishops. The Bishops house which has the date over it, a two story house, the Summers had it. A beautiful house. (Mr. Alcorn isn’t accurate here. The Bishop was the great-uncle of the four Almada de Alvarado boys, sons of Bishop Maria Antonio de la Reyes nephew, Antonio Almada and Luz Alvarado. The house originally belonged to the Alvarados) It’s up for sale again for one hundred. ($100,000) I wish I could buy it and put it together again. But I’m over that.

Leila: In the process of getting involved in the houses you’ve switched, bought and sold houses for many years, have you pared down your holdings now so that they’re not cumbersome or do you still have quite a little stuff around?

Mr. Alcorn: Well I became immigrate, immigrated, and I could have taken some of these properties in my own name. But I didn’t choose to for some reason or the other so I left everything in Anna Maria’s name. And truthfully I had another girl friend here for a number of years. And I gave her those two houses that she had and her house on the hill and I left everything else in Anna Maria’s name. It all boils down now that we only have this house, the hotel Portales, the Hotel Alamos, the two-storied building in front of the casino next to the bank and two or three little ones around and then I was going to do another big thing, this friend of mine from Pennsylvania, we got all excited about sub-division and we bought all the land between here and the second bridge, both sides of the road. Well, you know, you can have too much, and especially in a town like this, and there’s jealousy and so I split that up and I gave that to my daughters a couple of years ago or three, so each one of them has a piece of that. But you’d be surprised what that land is worth today. I can’t believe it! Why, they come here, someone has offered $20,000 for just one acre on the further end next to the last bridge on the left. And it’s just brush today; it’s all grown over.

I’m not now paying attention to anything. I was so fascinated. I had so much responsibility. (Speaking of Pennsylvania) In one year we made $3,000,000 worth of loans, to help low income and distressed farm families. Oh, I had a wonderful experience working for those people, yes. It was a lot of stress and I got to the point where I had these migraine headaches, once a week. I’ve had wonderful health since I came here. I think I would have died if I’d stayed there another year or two.

Leila: (I remarked how athletic Mr. Alcorn is, how remarkable it is.)

Mr. Alcorn: Well, in a sense it is. I’m 84. When you look around at other people the same age I think I’m doing pretty good. I met a good friend of mine in the street right in front of my house this morning. I’ll bet Pem Nuzum’s, he’s had these operations, poor Pem. I’m reading Gordon’s book. Maria Felix came here once. She wouldn’t let them have some things in the Museum here unless they’d dedicate one whole room to her. It was when they were gouged to put Lara in it. She came here and she offered $40,000 for a dish set that Adolpho Bley had. The first one is where they are fixing the roof. As we go down the Callejon there’s supposed to be a tunnel under the plaza to the hotel. The next one with about five arches, perhaps the caretaker is there. If you rap on the door and tell him that you’re an intimate friend of mine, please let you see whatever is convenient. He’s a good boy.

Leila: I asked if I could send them anything from Tucson, and he laughed and said, “Just write me a letter sometime.” We clasped hands and I left.

Levant Alcorn – 98 years old

August 6, 1905 – July 12, 2004